Ramuz’s daily life was highly ritualized, punctuated by strictly observed routines. Mornings were reserved for writing, afternoons for correspondence and visits. Once his project was established, Ramuz was able to write quickly, averaging up to ten sheets a day. The final manuscript of Derborence (231 pages), for example, was written in a month, and corrected in three weeks. The final manuscript of La Beauté sur la terre (363 pages), a particularly virtuosic novel, was conceived in a month and a half, and reread in a month. This writing phase was preceded by preparatory notes, plans and lists. It was followed by several rewriting phases, in typed versions and then on proofs.

If Ramuz composed his texts in such a concentrated way, it was because he could draw on a wealth of material that he had stored up over time, and to which he returned again and again, rewriting it in a different tone, or from a new angle. When he got down to work on a “definitive” manuscript, it was because he had found the right tone to ensure the novel’s harmony and coherence, and was ready to devote himself fully to the search for a rhythm that would structure his text from start to finish. In this crucial phase of his work, Ramuz concentrated on sound, sentence rhythm, orality, the way of handling the narrative, unfolding the tale as a storyteller would before their listeners.

« Solid work every day from 8 to 6. I am pressing ahead: thirty pages a day, on average, except today when I’m less lively. »

Diary, May 10, 1912

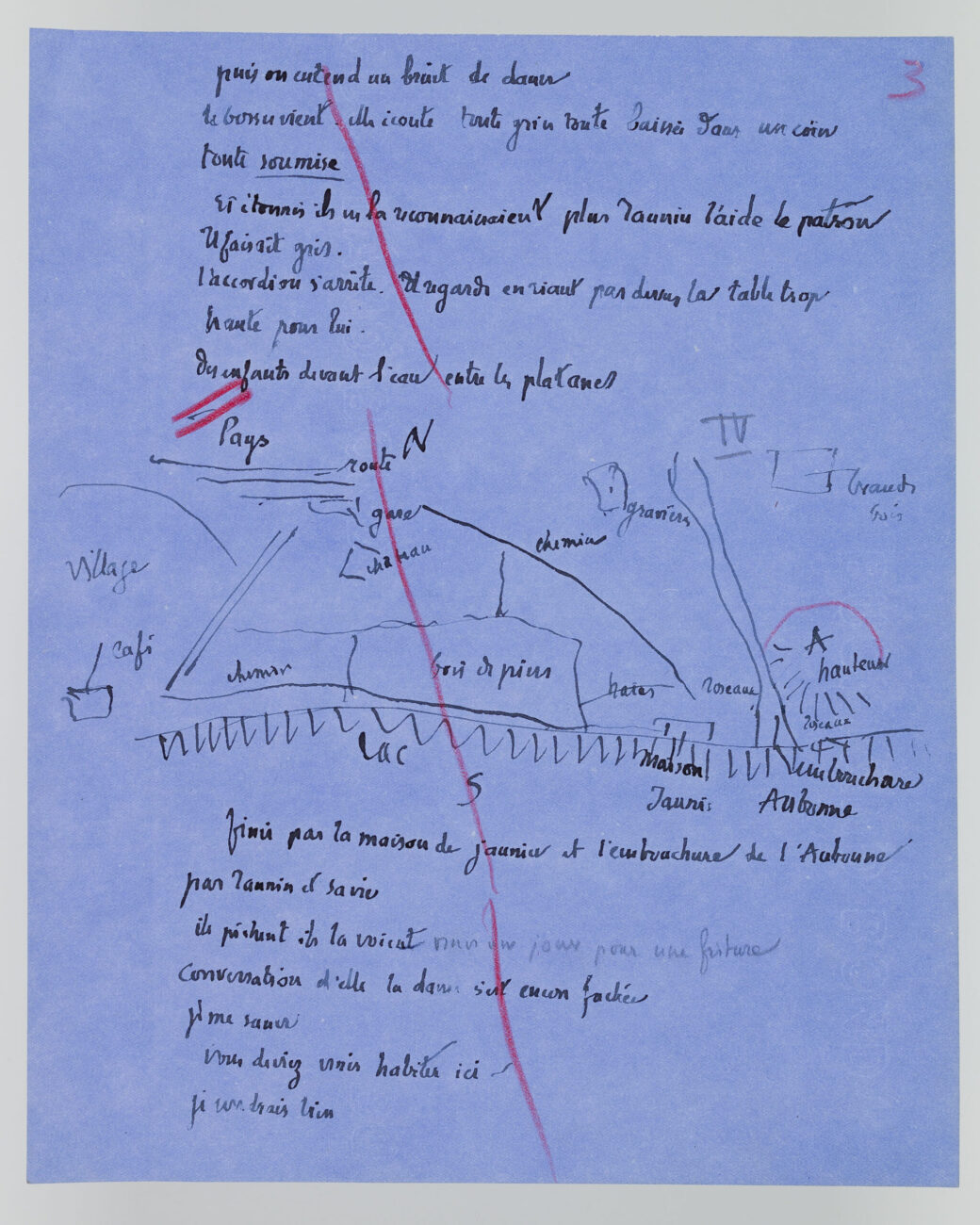

Caption

C. F. Ramuz (1878-1947)

Topographical plan used in writing La Beauté sur la Terre, 1926

25.2 x 20.3 cm

Collection C. F. Ramuz

BCUL, IS 5905/1/1/104

© BCU Lausanne (Laurent Dubois)