Style was Ramuz’s primary preoccupation, and indeed, other writers and critics have recognized him as a stylist of the first rank. Paul Claudel spoke admiringly of his “parlure” while Louis-Ferdinand Céline predicted that these qualities meant he would still be read in the year 2000. From the 1910s onwards, Ramuz developed a language of his own, in which orality played an increasingly important role. Regularly accused of writing badly, he clarified and defended his approach in his essays at the end of the 1920s. In these, he distinguishes between two French languages: the academic, standard language, the fine French language we learn at school and find in literature, which he calls “sign language” or “preserved French.” He contrasts this with a new language, which he tries to recreate from what he observes around him – a “gestural language,” an “open-air French.” Not a copy, pastiche or caricature, but the search for a living, moving, organic language.

I have written (I have tried to write) a spoken language: the language spoken by those of whom I was born. I have tried to use a gestural language that continued to be the one used around me, not the sign-language that was in books.

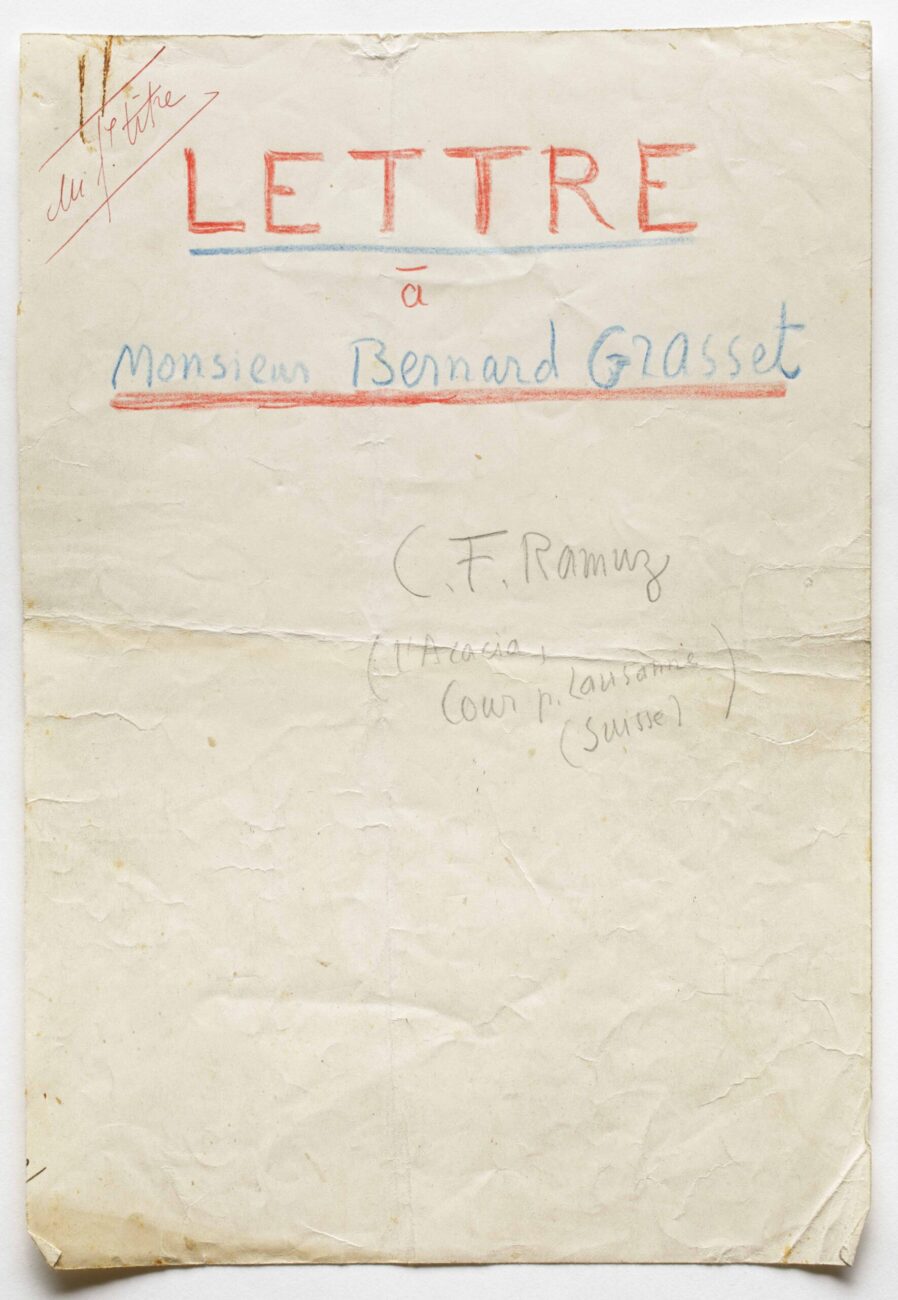

Letter to Bernard Grasset, 1929

Caption

Cover of typescript Letter to Bernard Grasset, c. 1929

Collection C. F. Ramuz, BCUL, IS 5905/1/5/267

Reproduction: Naomi Wenger